Notes on 20th and 21st

Century Literature

(1910-present)

Prose

Fiction (Novel and Short Story)

1910-1949 Regionalism, Nationalism, Novel of the

Mexican Revolution

Starting around 1910, the basis of

Latin American regionalism is set up as a combination of various elements;

namely, the triumph of earlier aspects of social realism, the innovative

language and style of modernismo, and

the poetical revolutions that occurred after World War I. What is most notable

in the prose of this period is a stronger sense of Latin American identity.

Writers perceive objective reality without economic or political

abstractionism. Gone, however, is the 19th century emphasis on the

detailed depiction of local customs that were thought of as picturesque,

typical, quaint. In the place of costumbrismo,

we find an increased awareness of the uniqueness and power of Latin American

nature. For example, one of the major writers of this period, Ciro Alegría

(Perú, 1909-1967; El mundo es ancho y

ajeno / Broad and Alien is the World,

1941), called attention to the "acción monstruosa de la naturaleza salvaje

frente a los conatos civilizadores

Some prominent

Latin American writers of prose fiction in this period are:

José

Eustacio Rivera (Colombia, 1889-1928) published his masterpiece, La vorágine, in 1924. Rivera was very active and accomplished man:

he taught in public high school (Escuela Normal Superior); he was a lawyer with

a law degree from the National University in Colombia; he held several public

prosecutor positions; he traveled to Perú and México as a diplomat; he served

on an international commission concerning border disputes between Colombia and

Venezuela; he was an inspector for Colombian oil fields; he explored the

interior regions (los llanos) and the

Orinoco River; and he died in New York City. Rivera's humanistic prose

expression, which comes out of the modernista

tradition, displays a marked tendency toward melodrama and exoticism, in which

he blurs the dividing line between fantasy and reality. In La vorágine, we are presented with a portrait of man (humans)

overwhelmed by the weight of nature in terms that show humans defeated in their

ferocious and epic struggle against nature. The atmosphere is that of

collective madness because the human characters are in direct contact with

uncontrollable forces of destruction.

Rómulo

Gallegos (Venezuela,

1884-1960) began literary writing after 1910, and his novels were all written

after 1920. His masterpiece, Doña Bárbara

(1929), is perhaps the most emblematic of the early twentieth century writers

in

Ricardo

Güiraldes (Argentina, 1886-1927) was a well-to-do writer with a European

cultural background who turned his attention to regional Latin American

traditions and scenes. He sought to create an authentic Argentinian literary

style and identity (i.e., una

argentinidad). In this pursuit he depicted rural people from the

Benito

Lynch (Argentina, 1885-1951) wrote about Argentinian gauchos not in a

mythical vein but rather as flesh and blood, three dimensional people; indeed,

he tended to view them as criminals. One of Lynch's most prominent works is El inglés de los huesos (The Englishman

of the Bones; 1924). In this novel Lynch, who himself had been immersed in

rural Argentinian life, achieves a kind of photographic realism via aesthetic

balance and a rather faithful reproduction of the authentic dialect and style

of the gauchos themselves. Whereas Güiraldes seems to wax nostalgic about

gauchos, Lynch projects his own first-hand knowledge of them. In Lynch's art,

there is, however, no vanguardism or impressionism because he followed directly

in the tradition of Spanish regionalism.

Eduardo

Barrios (Chile, 1884-1963) worked in the humanities areas of the novel,

short store, and theater. He was born in

Miguel Ángel Asturias

Rosales (Guatemala, 1899-1974). He

studied anthropology, history, and indigenous cultures in

Agustín Yánez (México, 1904 - 1980). In

addition to being a governor of the Mexican state of Jalisco and a college

professor, he was a major mid-century novelist. A product of the Latin American

middle-class intelligentsia, his philosophical outlook was consonant with the

enlightened European views following both World Wars. In other words, in his

works he adopted a new metaphysical style that he applied to a world that had

lost a sense of its organizational place in history. In the Mexican cultural

milieu he paints elegant narrative portraits of the conflict between Western

civilization and what has traditionally been seen as Latin American

"primitivism". This conflict plays out is terms of individual

consciousnesses. Yáñez' major novel is Al

filo

There

are, of course, many important Latin American writers during this period of the

first half of the twentieth century. Two more that should be mentioned in order

to complete this brief survey of the entire continent are Jorge Icaza (Ecuador, 1906-1978) and Ciro Alegría (Perú, 1909-1967 ). These two authors narrate

characters and societies from the Andean regions. Icaza's most notable novel is

Huasipungo (1934), which features

realistic language used to present social criticism from a Marxist

revolutionary ideological perspective. Like other works (prose narratives,

essays, theater), this novel sheds brutal light on the tragedy of Ecuatorian

indigenous peoples (Indians) by focusing on an native family that is forced to

accept its animal-like destiny. Characters include Indians stripped of their

land, cruel Occidental (i.e., Criollo, Spanish) exploiters. Icaza's goal is to

shock readers out of their apathy by means of literature that borders on

propaganda. Meanwhile, in Perú, Ciro Alegría was a member of the leftist

Peruvian political party APRA. He was exiled to

Mariano Azuela (México): see essay

about Azuela in: => Notes on the Humanities in the Mexican

Revolution.

José Rubén Romero (México): see essay

about Romero in: => Notes on the Humanities in the Mexican

Revolution.

Martín Luis Guzmán (México): : see

essay about Guzmán in: => Notes on the Humanities in the Mexican

Revolution.

Gregorio López y Fuentes (México): see

essay about López y Fuentes in: => Notes on the Humanities

in the Mexican Revolution.

1949-1999 Magical Realism (lo real maravilloso), the Latin American Boom, and Beyond

Alejo Carpentier (Cuba, 1904-1980). He was a major

Latin American and, of course, Cuban, musicologist, journalist, pianist,

ambassador, and writer, and most notably and lastingly, novelist. Although

Carpentier was born in La Habana of French and Russian parents at the beginning

of the twentieth century, his humanistic influence becomes truly significant at

mid-century. In 1921 he studied music and architecture, but he did not finish

those studies; the following year he published his first essays. From 1924 to

1928 he was the editor of the Cuban magazine Carteles. In 1927, as the founder of a minority anti-government

political party, he was jailed for his political activities against the

dictator Machado (=> Cuba).

For the following eleven years he lived in exile in

The

1949 introduction to El reino de este

mundo (The Kingdom of this World), a novel about the Haitian revolution,

the desire for freedom and justice, history, and imagination, is titled

"Problemática de la actual novela latinoamericana" (Questions about

the current Latin American novel), Carpentier discusses the challenges to

producing a novel in developing regions of the world such as Asia and Latin

America. In the essay he says this:

"In

a period characterized by a great interest in the Afro-Cuban folklore that was

"recently discovered" by my generation's intellectuals, I wrote a

novel—¡Ecue-Yamba-O!—whose characters

were blacks from the rural class of that period. I ought to point out that I

was raised in the Cuban countryside in contact with Black peasants and the

children of Black peasants. Later, I became very interested in the practices of

santería and ñañiguismo [secret Afro-Cuban religious beliefs], and I attended a

lot of their rituals and ceremonies. By means of such "documentary

research" I wrote a novel that was published in

Later

in this essay he says, in creating their works, Latin American humanists must

take into consideration a broad spectrum of what he calls contexts: racial,

ethnic, economic, political, culinary, musical, ideological, historical,

cultural, and stylistic. Furthermore, these humanists must account for lo ctónico (atemporal or inter-temporal

universality; chronological dislocations; see: => HUM 2461 Terms List), lo autóctono (what is autochthonous,

uniquely authentic in

"Light,

certain peculiarities of light, modify perspectives, values of distance,

placement of planes, in terms of the angle of observation taken by the Latin

American novelist. Light in Havana is not the same as Mexico's (there's an

enormous difference between both of them: in Mexico the light brings far

distances closer, but in Havana it makes what is nearer seem evanescent); nor

is light then same in Rio de Janeiro or Santiago de Chile, or even in

Port-au-Prince, where the presence of mountains that block the wind and the

clouds changes the values of illumination. To speak about the haze in

Now

we take a look at his essay on lo real

maravilloso published in Tientos y

diferencias. You can see this essay in either of these two formats:

HTM

format: => "About the Latin American real maravilloso".

PDF

format: => "About the Latin American real maravilloso".

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986;

Juan Rulfo (1917-1986; México) was born in

Jalisco, México as Juan Nepomuceno Carlos Pérez Rulfo Vizcaíno, but he is

universally known simply as Juan Rulfo. Until he was ten years old he lived in

a small pueblo with his grandfather, after which he lived in an orphanage. In

1934, he planned to attend the Universidad de Guadalajara, the great university

in the capital of

Gabriel García

Márquez (1927 -

2014; Colombia): for an introductory chronology of his life and works, see: => García Márquez

Mario Vargas Llosa (b. 1936; Perú) is one of the

original prose fiction writers and essayists of the famed “Generación del

Boom,” which began roughly in 1962 and spread throughout Latin America and

which became perhaps the most internationally renowned literary movement of all

time. Among his most famous novels are: La ciudad y los perros (1962); La

casa verde (1965); Conversación en la

Catedral (1970); Pantaleón y las

visitadoras (1973); La guerra del fin

del mundo (1985); El paraíso en la

otra esquina (2003); Travesuras de la

niña mala (2006). In

1990, he ran for the presidency of Perú, but he lost to the winner, the

presidential dictator, Alberto Fujimori. Among his many national and

international awards is the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010 and the (USA)

Library of Congress’s Living Legend award. In 2015 he published a book-length

book titled Notes on the Death of Culture, and in 2016 he published the novel

Cinco esquinas. His Brazilian war novel La

guerra del fin del mundo (1985) is acclaimed by many as his masterpiece. It

is based in part on the magnum opus by the Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha, Os Sertões (1902), which is about the brutal

civil war in the NE Brazilian backlands of Canudos. For an article on Vargas

Llosa’s appearance in Washington, D.C. on the occasion of his acceptance of the

Library of Congress award, see: => New York Times article “Love in the Time of

Spectacle” (< http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/14/books/mario-vargas-llosa-on-love-spectacle-and-becoming-a-legend.html?ref=arts>).

Other

prominent Latin American writers of prose fiction in this period are:

José

Guimarães Rosa (1908-1967;

José Lezama Lima (1910-1976; Cuba)

María

Luis Bombal (1910-1980; Chile)

José

María Arguedas (1911-1969; Perú): Los

ríos profundos (1962)

Ernesto

Sábato (b. 1911; Argentina): El túnel

(1948)

Jorge Amado (1912-2001;

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984; Argentina)

Elena

Garro (1916-1998; México)

Clarece

Lispector (1920-1977; Brazil)

Marco

Denevi (1922-1998; Argentina)

José

Donoso (1924-1996; Chile)

Rosario

Castellanos (1925-1974; México): Trayectoria

del polvo (1948); Balún Canán

(1957); Oficio de tinieblas (1962)

Carmen

Naranjo (b. 1928; Costa Rica)

Carlos

Fuentes (b. 1928; México)

Guillermo

Cabrera Infante (b. 1929; Cuba)

Elena

Poniatowska (b. 1932; México)

Mario

Vargas Llosa (b. 1936; Perú): La ciudad y

los perros (1962); La casa verde

(1965); Conversación en la Catedral

(1970); Pantaleón y las visitadoras

(1973); La guerra del fin del mundo (1985);

El paraíso en la otra esquina (2003);

Travesuras de la niña mala (2006).

Luis

Rafael Sánchez (b. 1936; Puerto Rico): La

guaracha del Macho Camacho

Rudolfo

Anaya (b. 1937; Aztlán)

Hernán

Castellano-Girón 1937-2016; Chile): Calducho

o las serpientes de la calle Ahumada (1998)

Marie-Claire

Blais (b. 1939; Québec)

Antonio Skármeta (b. 1940; Chile): El

cartero de Neruda (1985)

2001-present Post-Magical Realism and Twenty-first Century Prose Narrative

Some prominent

Latin American writers of prose fiction in this period are:

Julia Álvarez (b. 1950;

Laura Restrepo (b. 1950; Colombia): Delirio (2004)

Pedro Ángel Palou (b. 1966; Mexico): Zapata (2006)

Jorge Volpi (b. 1968; Mexico):A

pesar del oscuro silencio (1992); En busca de Klingsor (1999); La paz de los sepulcros (2006)

Junot Díaz (b.1968; Dominican

American; New York): The Brief Wondrous

Life of Oscar Wao (2007)

Hernán Castellano-Girón (1937-2016; Chile): Kraal (short

stories, 1965); El bosque de vidrio (short

stories, 1969); Nosferatu (film,

1973-1986); El automóvil celestial (poetry, 1977); Teoría del cuerpo pobre (poetry, 1978); Los

crepúsculos de Anthony Wayne Drive (poetry, bilingual, 1983); Otro cielo (poetry, 1985); El ilegible: las nubes y los años (novella,

1988); Calducho o las serpientes de la

calle Ahumada (novel, 1998); Un Orfeo

del Pacífico (Rosamel del Valle anthology, 2000); El huevo de Dios y otras historias (short stories, 2002); Nosferatu, una escenito criolla (film

script, 2009); Las palabras disperas (essay,

2010); Llamaradas de nafta (novel,

2012); Espectros (semi-autobiographical

novel, 2007-2012); El invernadero (novel,

2013); Coral de invierno (poetry,

bilingual edition, 2015);

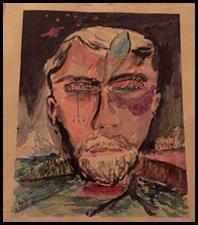

Hernán Castellano was born in

Coquimbo, Chile. He earned a doctorate at the University of Chile in Santiago

de Chile (in 1961 in Chile: título de

profesor) in chemistry and pharmacy. In 1967 he taught his specialization

(agronomical chemistry) at the University of Chile. At the time coup d’état by

Chile’s military under the command of Gen. Augusto Pinochet in September 1973

(dictator 1973-1990), Hernán Castellano-Girón was expelled from his position

and forced into exile. First he went to Italy, where he earned a graduate

degree (laurea) in Latin American

literature with a thesis (1981) on the Chilean writer Rosamel del Valle

(1901-1965). With a doctoral fellowship in hand, he went to Wayne State University

in Detroit where he earned a doctorate (1985). Next he got a full-time teaching

position at California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly, San Luis

Obispo), which hiring lead to tenure and promotion as a professor of Spanish,

Italian, and Latin American literature and humanities. He worked closely with

the department chair, William Little, and the major Chicana poet, Gloria

Velásquez. He was named the

poet laureate of this city. In 2007 he retired and returned to Chile, where he

bought a house (2008) on Isla Negra, where Pablo Neruda had his famous seaside

home. In addition to being a poet, he was a writer of prose fiction (short

stories, micro-stories, and novels), an award-winning essayist, winning a

Chilean national prize for an essay on Neruda, film maker, and painter. His

film, Nosferatu, is a Dracula-like

story based on Bram Stoker’s original novel and featuring an insane priest. Dr.

Ana Balakian, professor of French and comparative literature at New York University,

in her 1978 book on surrealism, said that Hernán Castellano was “the last of

the surrealists.” His paintings, which have a world-wide circulation and which

have been used as the illustration on many Spanish-language book covers,

certainly support Balakian’s assessment. About himself Hernán Castellano said

that his nearly unrecognized presence in Latin American literature was “pretty

secret” (“un escritor casi secreto”)

which was due to his “greatest sin, that he was original:” “ser original, llevar adelante un discurso

que no calza con ninguna de las líneas aceptadas y aceptables sobre todo in

narrativa” [to be original, to undertake a discourse style that does not

accord with any of the acceptable or accepted patterns, above all in

narrative]. As an example of his art here is one of his self-portraits:

Leonardo Padura (b.

1955; Cuba): Pasado perfecto (1991;

trans. 2007: Havana Blue); Vientos de cuaresma (1994; trans. Havana Gold, 2008); Máscaras (1997; trans. Havana

Red, 2005); Paisaje de otoño 1998;

trans. Havana Black, 2006); La novela de mi vida (2002); Adiós, Hemingway (2006); El hombre que amaba los perros (2009); Herejes (2014).

Padura is one of the most

prominent and talented of Latin America’s novelists since the last decade of

the 20th century and into the 21st century. He is an essayist,

short story writer, literary critic, and novelist. He came to prominence with

the first for novels, published from 1991 to 1998; they are known collectively

as the Four Seasons. These are sophisticated literature written fully within

the classical conventions of detective novels; that is the roman noir. Their protagonist is a Havana tireless and cynical

police detective, Mario Conde, who investigates murders in Havana, murders that

touch on some of the most explosive issues in communist Cuba, crimes that

involve corruption in the government and in the police department. Since Padura

never mentions the Cuban leadership by name, and since he never explicitly

denounced the regime, he has been able to explore the gritty realities of Cuban

life under the Castro regime without suffering—except for a two-year period in

the 1970’s—the ostracism, imprisonment, or exile that hundreds of other Cuban

members of the intelligentsia have suffered since 1959. Padura continues to

live in the home in which he was born in the suburbs of Havana with his wife

and two dogs.

Roberto Bolaño (1953 – 2003;

Chile) is perhaps

the most dynamic Latin American writer at the turn of the 21st

century.

|

|

Throughout his life he lived

variously in Chile, Mexico, El Salvador, France, and Spain. He was born in

Santiago, Chile. A dyslexic young man who had trouble in school, his

family moved to Mexico City in 1968; he then dropped out of school taking jobs

as a reporter and moving in activist left-wing political movements, which, in

Mexico at the time were nearly revolutionary (see: Generation of ’68).

According to his own account—which several commentators have called into

question—he returned to Chile in 1973 during the time of Augusto Pinochet’s

military coup against the democratic government of president Salvador Allende

(1970-1973). Bolaño said that he was arrested and spent a week in jail, from

whence he was rescued by friends who were prison guards. He narrates this

semi-autobiographical episode in his short story “Dance Card.” During the 1970s

he became an avowed Trotskyite, founded a minor literary movement he called infrarrealismo (sub-realism), but in his

novel Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives; 1998) he parodied

his own literary movement. For a time he worked with the left-wing guerrilleros

in the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front in during the civil war in El

Salvador. Afterwards he returned to Mexico, where he was a misfit poet—what

some have called a “literary enfant

terrible.” It is possible, at least according to his own account, that he

was addicted to heroin. In 1977, he moved to Spain, settled in the Catalan

village of Blanes, married, and had a son, who was born in 1990. In Blanes, he

had various odd jobs in cafés, campgrounds, hotels, and garbage collection

agencies. After his son was born he switched from poetry to narrative fiction

because, as he explained, he could earn a living publishing fiction and he felt

he could live more responsibly as a novelist than as a bohemian poet.

Nevertheless, in 2000, his collected poetry was published in a volume titled Los

perros románticos: Poemas 1980-1998 (The Romantic Dogs).

In 1989,

living on the Catalan coast in Spain, he wrote the novel El tercer Reich (published posthumously in 2010 (Editorial

Anagrama, Barcelona). In Bolaño’s unique combination of content and style—which

we shall call post-post-modern—he evokes the desultory late summer feel in a

small tourist town on the Spanish Mediterranean region of the Costa Brava. The

contemporary plot centers on a young German (Ugo Berger) who is the German

national champion player of a complex board game called, in English, “The Third

Reich.” The protagonist spend his German vacation in a seaside hotel owned by a

German couple where, ten years earlier his family had stayed in the same hotel.

His vacation project in the unnamed coastal town is to write an expert article

on new strategies for the game, strategies designed for the Nazi side in World

War II to win the game. The novel’s almost painfully slow-paced and obsessive

narrative features the use of quasi-realistic psychological and physical detail

that inverts traditional realism in such a way that the reader simultaneously

understands and is puzzled by what is described. The over-all result points to

one of Bolaño’s signal contributions to Latin American prose fiction at the

turn of the 21st century: his grand theme of the perverse attraction

of Nazism, gaming, and the sense that the elusive quality of literature

(fiction, narrative) is the only grounded reality.

Bolaño died

in 2003 of a protracted struggle with liver failure. His monumental work, the

five-part novel 2666, was published

posthumously the following year. Bolaño’s literary prominence rests on his work

from 1989 to his death. His main works are Los detectives salvajes (1999), Nocturno de Chile (a short

novel; the Rómulo Gallegos Prize in 1999), 2666, and two short story

collections, Llamadas telefónicas and Putas asesinas. In 2009, more unpublished novels and other

works were discovered, among which was El tercer Reich. It is rumored in

the literary world that a sixth and final section of 2666 may be

published.

Bolaño’s

masterpiece, 2666, is a massive novel

divided in five sections. The plot moves toward the historically true serial murders

of prostitutes in Ciudad Juárez, a teeming Mexican city across the Río Bravo

del Norte (Río Grande) from El Paso, Texas. The English translation by Natasha

Wimmer won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction in 2008. In his

article in The New York Review of Books, the critic Francisco Goldman says this

about 2666: “[It is an] often

shockingly raunchy and violent tour de force (though the phrase seems hardly

adequate to describe the novel’s narrative velocity, polyphonic range,

inventiveness, and bravery) based in part on the still unsolved murders of

hundreds of women in Ciudad Juárez, in the Sonora Desert of Mexico.”

If anything,

2666 is a work of protean

proportions. One of Bolaño’s friends,

Rodrigo Fresán, has called it a novela

cósmica (El País, Madrid). Another critic says that it combines vaudeville, academic

fiction, pulp fiction, science fiction, and even war literature (Minh Tran Huy,

in Le Magazine Littéraire, Paris). As dark and disturbing as much of the

material in it is—and it is truly so—it is also a pleasure to read because of

Bolaño’s mastery of the creative expanse of the contemporary Spanish language

and its dialects. The style leaps from cryptic to periodic in the extreme, and

the tone ranges, often within single sentences, from deadly serious to wildly

comical. Since this novel is set in Italy, England, France, Spain, Chile, the

United States, and, finally, Mexico, a question arises concerning its place and

Bolaño’s place in Latin American humanities. Clearly, Bolaño’s oeuvre grow out

of the movements of the Generation of the Boom and lo real maravilloso (Magical Realism). And because the author lived

most of his adult life outside his home country, his works have international

settings and they appeal to a vast international audience. In this regard,

then, he belongs to the humanistic and political generation the Chilean

diasporic exile that began in 1973. Even so, his works are significant because

they are paradoxically Latin American in a traditional sense while at the same

time they remain, as he himself would have it, so it seems, heterodox and

eccentric. In his article on “Roberto Bolaño’s Ascent” in The Chronicle Review

(December 19, 2008), Professor Ilan Stavans concludes with these two

paragraphs:

“Bolaño

didn’t hold academic life in any esteem. Knowledge, his work suggests, comes to

us in chaotic ways, when we least expect it. Whenever he portrays academics,

they are dissatisfied types, looking for signs of intelligence everywhere but

in their own profession. The model student for Bolaño is irreverent,

intolerant, and self-taught.

Indeed, I

doubt that a novel like 2666 can be taught, for it begs to be found by readers

in an accidental fashion, without instruction. Therein may lie the lesson to be

learned from Bolaño: Rebellion and success do not rest easily with each other

(21).

For a

discussion of the cover of the first editions of the Spanish and English

versions and for a passage from 2666, click on the following image:

Among recent

English translations of his works are: By

Night in Chile, trans. Chris Andrews (2003); Distant Star, trans. Chris Andrews (2004); Last Evenings on Earth, trans. Chris Andrews (2006); The Savage Detectives, trans. Natasha

Wimmer (2007); Nazi Literatures in the

Americas, trans. Chris Andrews (2008); The

Romantic Dogs: 1980-1998, trans. Laura Healy (2008); 2666, trans. Natasha Wimmer (2008); The Skating Rink (2009).

In 2010, an

English translation by Chris Andres of Bolaño’s 1999 Spanish-language short

novel Monsieur Pain was published by

New Directions. In his New York Times (February 7, 2010), Will Blythe concludes

by saying this about Monsieur Pain:

“By contrast, the evil in “Monsieur Pain” feels ominously real, despite the

fact that Bolaño hardly enunciates its presence. The novel melds existential

anxiety to political terror in a measure peculiar to Bolaño—imagine the

protagonist of Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart” if he were being interrogated by the

secret police on suspicion of having hidden subversives behind his wall.

Readers know, as the characters of “Monsieur Pain” do not, that Paris in 1938

is a city of sleepwalkers, that a darkness soon comes its way. It is Bolaño’s

great gift to make us feel the dimensions of this darkness even when we cannot

see exactly what it hides” (Book Review, 7).

Daniel Alarcón (b. 1977; Lima, Perú) is one of a new generation of bi-cultural,

bi-national (Perú and U.S.A.) Latino / Latin American writers. In this sense he

is fully representative of a 21st century turn (cambio de coyuntura) in Latin American literature (and the

humanities in general). His Peruvian parents moved to the United States when he

was three years old where he grew up Birmingham, Alabama, in a middle class

setting. He has a B.A. degree in Anthropology from Columbia University and an

M.A. from the Iowa Writers Workshop. He now lives in San Francisco where he lives

with his wife Carolina. He has been a visiting writer at several American

colleges including the University of California at Berkeley. In addition, he is

the editor of the Peruvian magazine Etiqueta Negra.

|

|

Principally, he is an American

writer of prose fiction (novel and short story) and essays, who writes in

English. Among these English-language works are War by Candlelight: Stories (2005; finalist for the 2006 PEN/Hemingway

Award), Lost City Radio (2007:

translated into 10 languages), and At

Night We Walk in Circles (2013). In addition, he has published

English-language short stories in periodicals such as The New Yorker, Virginia

Quarterly Review, and Granta. Issue

no. 97 of Granta, which was dedicated to the best young American novelists, he

published “The King is Always Above the People” (2007). In the June, 2003 issue of The New Yorker, he

published “City of Clowns,” which he translated and partially rewrote in a

Spanish-language graphic novel, titled Ciudad

de payasos (2010), with graphic artwork by the award-winning Peruvian

artist Sheila Alvarado. In 2011 he founded a bilingual pan-Latin-American

podcast in Spanish and English, Radio Ambulante (<http://radioambulante.org/en/>),

which is dedicated to telling Latin American stories. In Spanish he published

the novel by the same (translated) title as the 2007 story in Granta:

El rey está por encima del pueblo

(2009). Most of his other works have also been published by major Spanish

language publishing houses.

Written and published originally

in English as At Night We Walk in Circles,

it was translated by Jorge Cornejo Calle and published by the Spanish

publishing house of Seix Barral in 2014 as De

noche andamos en círculos. In structure, style, content, an aesthetic

style, which we could call post-post-modern in the manner of the Chilean—yet,

international Spanish language writer—Roberto Bolaño (see above), this novel is

a first-person narrative by a ever-present narrator who does not become a

character in his own narration until the plot nears its dénouement. Ostensibly,

the work we are reading is the product of the narrator’s research into a young

Peruvian actor, Nelson, who becomes entangled in the kind of everyday events

and inadvertent missteps that eventually lead him to end in a maximum security

Peruvian prison for a murder he did not commit. The setting moves from actors

in Lima to deep Andean provincial towns and back to the capital. The action

moves from an itinerant theater troupe to the triangle of the jealousies of two

young men in love with the same woman, to a Nelson’s impersonation of a dead

son in a rural home in the Andes, to the violent death of Nelson’s rival at the

hands of anonymous bullies in the dark streets of Lima, to Nelson’s trial and

imprisonment. The narration centers on the “slippage” between the narrator’s

objective description of events and places and the interspersed speech of

various people whom the narrator interviews in an attempt to compose a

resemblance of the character of the ill-fated actor who psychology is easily

recognized by 21st century readers anywhere in the world.

In the June, 2003 issue of The

New Yorker, he published “City of Clowns,” which he translated and partially

rewrote in a Spanish-language graphic novel, titled Ciudad de payasos (2010), with graphic artwork by the award-winning

Peruvian artist Sheila Alvarado. In this novel a young urban Peruvian

journalist copes with the death of his father while researching street clowns

in Lima. While the main characters are the journalist, his mother, and one

particular clown who introduces the journalist first-hand into the sad-happy

life of being a street clown, the city of Lima is at the same time backdrop and

character in the work. For a few more details about this graphic novel, click

on the following image:

Poetry

1916-1949 Vanguardismo,

creacionismo, and various avant-garde

movements such as ultraísmo

After the death of the great modernista poet Rubén Darío in 1916, many

Latin American writers, and most notably the poets, reacted against modernismo, a vein of writing that for

them had run out of creativity and that no longer reflected the social,

political, psychological, and artistic realities of the early twentieth century.

Most notably, this new generation of poets felt the influence of the new

currents of art and poetry that had begun in

In general, the term Vanguard

refers to a number of so-called "isms", each of which often sprang

from a dogmatic manifesto or declaration of principles, and each of these

movements had manifestations throughout the humanities (theater, art,

literature, movies, music, architecture, etc.). This is especially true because

one of the prime aspects of vanguardist movements is the mutual inspiration and

fertilization across the traditional disciplinary boundaries of various

humanistic disciplines.

Several factors cause Latin

American vanguardismo to be

distinguished from other similar movements in European and the

Some

prominent Latin American poets in this period are:

Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957, a posmodernista

from Chile)

César

Vallejo (1892-1938, Perú)

Juana de

Ibarbourou (1892-1979, Uruguay)

Vicente

Huidobro (1893-1948, Chile)

Luis

Palés Matos (1898-1959, Puerto Rico)

Nicolás Guillén (1902-1989, Cuba)

Poet, journalist, political liberal, Nicolás Guillén (Nicolás Cristóbal Guillén

Batista) is generally considered, after José Martí, Cuba’s national poet. His father and mother were both

Afro-Hispanic Cubans. Much of his writing, especially his poetry, focuses on

blacks in Cuba and Afro-Cuban culture and the hybrid Cuban religion of

Santería, which is a fusion of Roman Catholicism and the Yoruba religion. His

early poetry was influenced by the black American poet, Langston Hughes, whom

he met in 1930. His poetry was also heavily influenced by Cuban son music. He was jailed in 1936 for his

political activism following the overthrow of Cuba’s dictator Gen. Gerardo

Machado (1933). Thereafter, Guillén joined the Cuban Communist Party. As a

journalist, he covered the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) as a support of

Spain’s democratic Republic. From 1940 to 1959 he travelled widely in South

America, and China. In 1954, he was awared the Stalin Peace Prize. From 1961 to

1986 he was the president of Cuba’s Unión Nacional de Escritores (UNEAC). In

1983, he was the first winner of Cuba’s National Prize for Literature. Among

his major works are Motivos de son

(1930), Sóngoro cosongo (1931), Elegías (1948-1958), Poemas de amor (1964), and El diario que a diario (1972). For one of his finest poems, see:

=> Sensemayá.

Pablo Neruda (1904-1973, Chile)

|

|

Born

in

For a year-by-year chronology of

major events in Neruda's life, click here: =>

Neruda Chronology.

For an on-line PowerPoint program

of "Heights of Machu Picchu" (Alturas de Machu Picchu) in Spanish,

click here: => Alturas de Machu Picchu.

Jorge Amado (1912-present, Brazil)

Ernesto

Cardenal (1925-present, Nicaragua)

|

|

Born in the city of Granada,

Nicaragua, in 1925, in an upper class family, Ernesto Cardenal is a Catholic

priest, a proponent of liberation theology (la

teología de la liberación), and one of the most important Latin American

poets of the last half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the

twenty-first century. From 1946 through 1950 he traveled to

The first phase of Cardenal's

work is love poetry in the modes of romanticism and bitterness. In his second

phase, he writes very modern verse in which he moves freely among themes of

political protest, social injustice, popular culture, pre-Columbian mythology,

current events, humanitarian causes, advanced scientific knowledge, and the new

Latin American Catholic movement of liberation theology. Among his most notable

works are Gethsemany, KY (1960), Epigramas: poemas (1961), Hora cero (1965), Oración por Marilyn Monroe (1965), Salmos (1967), and Cántico

cósmico (1989).

Enrique Lihn (1929-1988, Chile)

Alurista

(1947-present, Aztlán)

Raúl Zurita (1950-present, Chile)

Major Women Poets:

Gloria Anzaldúa (1942-1904, Aztlán)

Sandra

Cisneros (1954-present, Aztlán)

Nancy

Morejón (1944-present, Cuba)

|

|

This major

Cuban writer and poet was born and educated in Havana, and she has prospered and

remained in Cuba throughout the Cuban Revolution. Her self-acknowledged ethnic

mix or blending of an African father and Chinese-European mother figures

prominently in her identity and her works; however, her primary identity is

that of an Afro-Caribbean or Afro-Cuban woman. She graduated from the

University of Havana in European, Caribbean, and Cuban literature, and she is

fluent in Spanish, English, and French. In fact, she is a talented translator

from French and English to Spanish. In addition to poetry, her primary genre,

she also writes in the fields of journalism, literary criticism, and theater.

Significantly, some critics regard her as the inheritor of the Nicolás Guillén,

a famous post-Surrealist Afro-Cuban poet. She has won a number of prizes, and

she has travelled fairly extensively through Europe and the United States.

For an important critical look as

the sexual life of Cuban women from 1959 to 2012, see: Carrie Hamilton, Sexual Revolutions in Cuba; Passion,

Politics, and Memory (2012).

For perhaps her most famous work,

an eloquent statement about the trajectory of a Cuban black African slave

experience from captivity to communism, see her poem: => “Mujer negra” / “Black

Woman.” (Spanish version) (English translation).

Drama

1920-2007 Theater

Some

prominent Latin American playwrights in this period are:

Osvaldo Dragún (Argentina)

Emilio

Carballido (México)

Luis

Valdés (Aztlán)

René

Marqués (Puerto Rico)